Author:

IBC’s Team

10 September 2024

Sustainable taxonomies serve as comprehensive classification systems that allow policy makers and investors to integrate climate change and broader sustainability concerns into their decision making. The urgent need for a “greener” taxonomy stemmed from the absence of green sector criteria standards that can support sustainable finance policies. From the supervisory side, such taxonomy is needed to promote the green sector’s data integration including to assess financial, climate-related and broader environmental risks (physical risks and transition risks).

Benefits of sustainable taxonomies for the market could be divided into two types:

- Market clarity, meaning more precise and consistent definitions of which investments are “green” and “sustainable” could facilitate the mobilization and reallocation of financial capital towards those green and sustainable investments. It could give confidence and assurance to investors that they know what they are investing in, and know that their investments will be recognised as green or sustainable. Increased market clarity can in turn result in cost savings by reducing due diligence costs.

- Market integrity, by avoiding sustainability bubbles as a general aim of sustainable finance definitions, is to attract capital to investment objectives. Sustainable investment opportunities will depend on their risk-return profile, which is affected by such considerations as the current state of regulation and policies, such as carbon pricing. The availability of finance at the right cost plays a role, but may not suffice to shift capital towards a sustainable economy if other sustainability policies are not implemented.

These potential benefits mean that policy-makers could consider how potential market growth in response to taxonomy development would match up against emerging supply of sustainability projects and assets, and aim to develop stronger targets, policies and implementation in parallel with the development and implementation of taxonomies. Taxonomies have the potential to be a powerful toolkit but they are complementary to, and not a substitute for, the need for strategic planning, good policies and regulations, e.g. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), national interests/initiatives, such as Nationally-Determined Contributions (NDC) Implementation Roadmap, Net Zero Emissions (NZE) Roadmap, Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) and downstream initiative.

In Indonesia, sustainable taxonomy is termed as Taksonomi Berkelanjutan Indonesia (TBI), which adhere the principles of:

- Scientific credibility, by considering best practices in policy, knowledge and technology at national and international levels;

- Interoperability and national goal-oriented, whereby implementation is ought to be relevant on international and regional levels for facilitating Indonesia’s gradual and just transition; and

- Inclusive, meaning it is designed to be implementable in various circumstances of corporations and smaller sized enterprises.

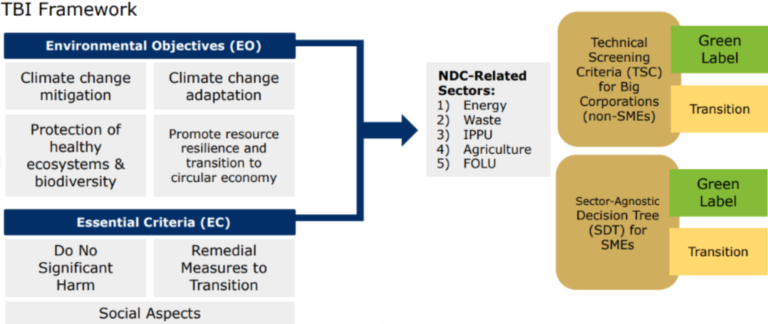

A gradual transition started in 2023 beginning with the energy sector, however, for this TBI. It is in line with the energy transition agenda declared in the 2022 G20 Indonesia Presidency and ASEAN Chairmanship by Indonesia in the following year. The following figure describes the framework of TBI in one picture.

The new TBI features include the Environmental Objectives (EO) of climate change mitigation (decarbonization), adaptation (minimizing impacts), healthy ecosystems and biodiversity protection, resource resilience protection and circular economy transition. The Essential Criteria (EC) for such EO are “do no significant harm” (activity cannot pose disadvantages to other EO), “remedial measures to transition” (potential disadvantage is minimized if any), and fulfilling “social aspects” such as human rights, safe labor, gender equality and poverty alleviation. Sector wise, those included in the NDC, which are energy, waste, industrial process and production use (IPPU), agriculture and forest and other land use (FOLU). The taxonomy itself is then categorized as green, yellow, red, and in transition.

The interesting aspect of this TBI is that it facilitates “transition label”, whereby activities are still not aligned with green commitments but are already in transition toward green in a certain time frame, facilitates emission reduction in short and medium term, encouraging other sustainable activities while still fulfilling social aspects.

In terms of the emissions-related criteria, TBI uses quantitative and qualitative approaches to define cross-classification boundaries to prevent ambiguity and greenwashing. Quantitatively, one of the criterias settle emission caps using a direct emissions approach. The initiative to develop pricing in carbon exchange and green bond standard is also supported during the process. In the implementation, corporates will be using Technical Screening Criteria (TSC) approach, while the SMEs use Sector-agnostic Decision Tree (SDT).

TSC, or Kriteria Teknis (KT), is a set of criteria used to assess if the activity has contributed to the economy and fulfilled the EOs or not. Three types of KT:

- Nature of the Activity/Direct Green: An activity is regarded to be automatically into the classification once it can be proven to support net zero emission.

- Quantitative:

- Impact based/relative improvement

- Environmental performance

- Best in Class performance

- Qualitative:

- Practice Based

- Process Based

The use of KT itself covers activities in the taxonomy, categorized in any of the 5 NDC-Related sectors in the corporation level, and other activities specific to the taxonomy.

SDT, is an assessment approach that is principle-based through a decision tree made with specific environment objectives and guiding questions. Utilization of SDT covers activities specified on the taxonomy with 5 NDC-related sectors in the scale of SMEs and also other activities specific to the taxonomy.

In coming up with these methodologies, the development of TBI learned from other established taxonomies, among them are China and ASEAN.

Case in point: China

China is the largest coal consumer and emitter of greenhouse gasses in the world. High levels of local air pollution have become a significant concern. In 2006, the Chinese government decided to promote environmental insurance strongly. In 2007, the 17th national congress of the Communist Party of China proposed in 2007 the construction of an “eco-civilization”. In 2008, the government started national trial applications of pollution insurance in several cities and provinces. Since then, environmental issues have received even more attention.

In terms of financial regulation, China has three main frameworks for green finance definitions. The core framework is the “Guiding catalog for the green industry”. Originally established in 2016 and updated in 2019, this framework is the joint production of seven ministries and related commissions, namely the NDRC (planning ministry), the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC, the central bank), the financial regulators of respectively the banking sector (China Banking Regulatory Commission, CBRC), the securities sector (China Securities Regulatory Commission, CSRC) and the insurance sector (China Insurance Regulatory Commission, CIRC).

For lending, the CBRC issued in 2012 and subsequent years green credit guidelines, key performance indicators for green credit and green credit statistics forms. For green bonds, the PBOC issued a “green bond endorsed project catalog” in 2015, which is often referred to as “the Chinese green bond taxonomy”.

This taxonomy is then divided into energy savings, pollution prevention and control, resource conservation and recycling, clean transportation, clean energy, ecological protection and climate change adaptation.

Case in point: ASEAN

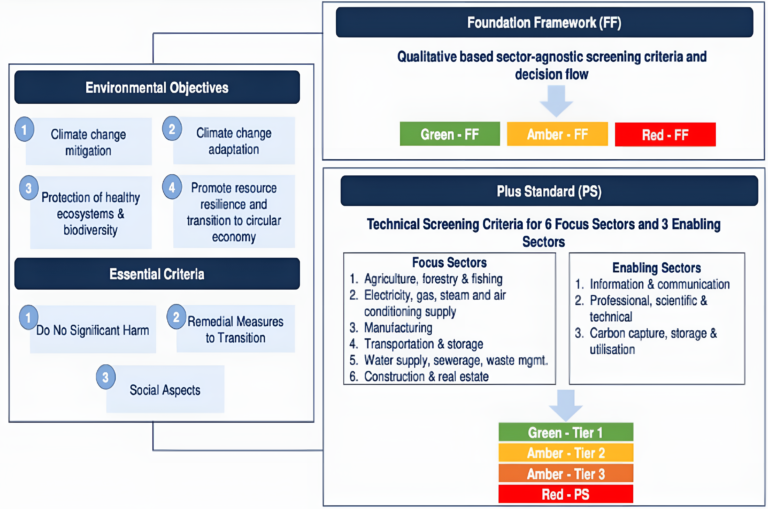

The ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (ATSF) has been designed to be, as much as possible, interoperable with taxonomies used in other jurisdictions. ATSF upholds the principles of being the overarching, inclusive guide for all ASEAN Member States’ national goals, taking into account other relevant global taxonomies that are science-based, and credibly aligned with sustainability initiatives taken by the capital market, banking and insurance sectors. The following figure describes the structure of the ATSF.

ATSF is used for various different purposes by companies and regulators. The following table explains such use cases, divided into activity categories.

Categories | Use Case by Companies | Use Case by Regulators |

Bond issuance | Applied directly in issuance and reporting credentials | Applied when setting requirements for green bonds |

Sustainable investees identification | Reference for self-assessing feasibility of receiving potential investment funds and promoting green credentials to potential investors | Referred to when setting requirements for “sustainable” investment funds |

Sustainable lending products development or eligible borrowers identification | Reference for self-assessing feasibility of receiving potential green/sustainability loans and promoting green credentials to potential lenders | Referred to when setting requirements for green loans in the member states |

ESG benchmarks/indices definition and constituents identification | Reference for self-assessing feasibility of being selected for ESG benchmarks and promoting green credentials to ESG benchmark administrators and investors | Referred to when setting requirements for ESG benchmarks |

Corporate sustainability reporting | Applied in demonstrating green credentials without risk of greenwashing, improving competitiveness and attractiveness to sustainable investors and lenders, and improving sustainability-related risk management | Reference for setting rules on corporate sustainability disclosures and ESG risk management practices |

Financial market participant sustainability reporting | N/A | Reference when setting rules for the financial market participant sustainability reporting disclosures at portfolio and product level |

Transition finance | Applied to adapt business models and strategies that meet the demand of transition to low-carbon and sustainable economies | Referred to ensure accurate reporting on the environmental impact of transition finance activities and adherence to relevant regulatory requirements |

One of the new things and, for the first time, considered in the second version of the ASEAN Taxonomy is the gradual termination of coal-fired power plant operations as an effort to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions to achieve the target of the Paris Agreement. The discontinuation of coal-fired power plants (CFPP) procedure s will facilitate the diversity of understanding of ASEAN member countries regarding an equitable energy transition. The ATSF also includes TSC for energy transition financing, including the termination of coal-fired power plants, into the Green and Yellow categories. In ATSF, TSC forms the basis for assessing the classification of whether an activity is Green (very important contribution to environmental goals); Amber (does not meet Green criteria but shows progressive steps to achieve sustainable ASEAN development) or Red (not adhering to environmental goals).

In summary, Indonesia’s TBI could learn lessons from China and ASEAN Sustainable Taxonomies that such taxonomies ought to be doable with guidance, possess both qualitative and quantitative standardized calculators for each EOs and ECs, whereby stakeholder added benefits are evident, and is interoperable to increase coverage and impact. Yet, Indonesia must also clearly determine its direction of whether to have its sustainable taxonomy going international or looking inwards (national ecosystem). While the former strengthens interoperability and opens up the possibility of international investments at the cost of higher corporate standards, the latter strengthens national sentiments and makes classifications more actionable for corporations because of more lax standards, although receiving international investments might prove to be more difficult.