Author:

ReservoAir and Indonesian Business Council

6 May 2025

This article is in collaboration with:

Water crisis in an urban area: A data

Over a half of the global population now lives in cities, a figure expected to rise to two-third by 2025. The rapid urbanization brings significant challenges–including poverty, environmental degradation, and most pressingly, a growing water crisis (National Geographic, n.d.).

More than one billion urban dwellers are predicted to face water shortages in the near future (Flörke, M., Schneider, C., & McDonald, R. I., 2018). Due to droughts and irresponsible water extraction practices, over 80 major cities worldwide have experienced severe water shortages within the last 20 years (Zhang, X., et al., 2019). The 4.4 billion people who live in towns and cities, particularly in low-income nations, are on the front lines of the 90% of climate disasters that now occur that are related to water. Other data shows that major climate-related disruptions, such as floods, droughts, and surface flooding, were documented in 85% of cities (CDP, 2019).

Urban flood in Indonesia: an example of water crisis

The water crisis has also taken root in Indonesia, where urban flooding is becoming increasingly frequent and severe. According to the latest data from BNPB, a total of 852 disaster events have been recorded in 2025, with floods accounting for approximately 67% of these incidents. As witnessed on March 2nd, 2025, extreme rainfall in Bogor triggered flooding throughout Jabodetabek area, affecting over 125,000 people across six cities and causing economic losses estimated at IDR 5 trillion (USD 300 million) (Alam, K. A., et all., 2025).

The severity of floods in the Jabodetabek area is not a new phenomenon. A similar extreme event took place during the New Year of 2020, when heavy rainfall affected many parts of Jabodetabek, including Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi. The flood was caused by the overflowing of rivers which originate in Bogor, particularly in Puncak areas. At least 66 people were reported to have died as a result of the disaster (DetikNews, 2020).

Comprehensive solutions to the water problem

It is crucial to understand that these disasters do not occur in isolation; rather, they are heavily influenced by complex interplay between natural and human factors—ranging from topography, rainfall, land use, and urban planning. Given the complexity of the issue, a comprehensive and integrated approach—commonly known as Integrated Flood Solutions—is essential. This approach involves considering the entire watershed or river basin as a unified system. In the upstream area, land use should prioritize conservation and natural protection. In the middle of a river basin, erosion controls and water retain infrastructures should be emphasized. For the downstream area, the focus should be on improving the efficiency of urban drainage systems, while also building a disaster-resilient society.

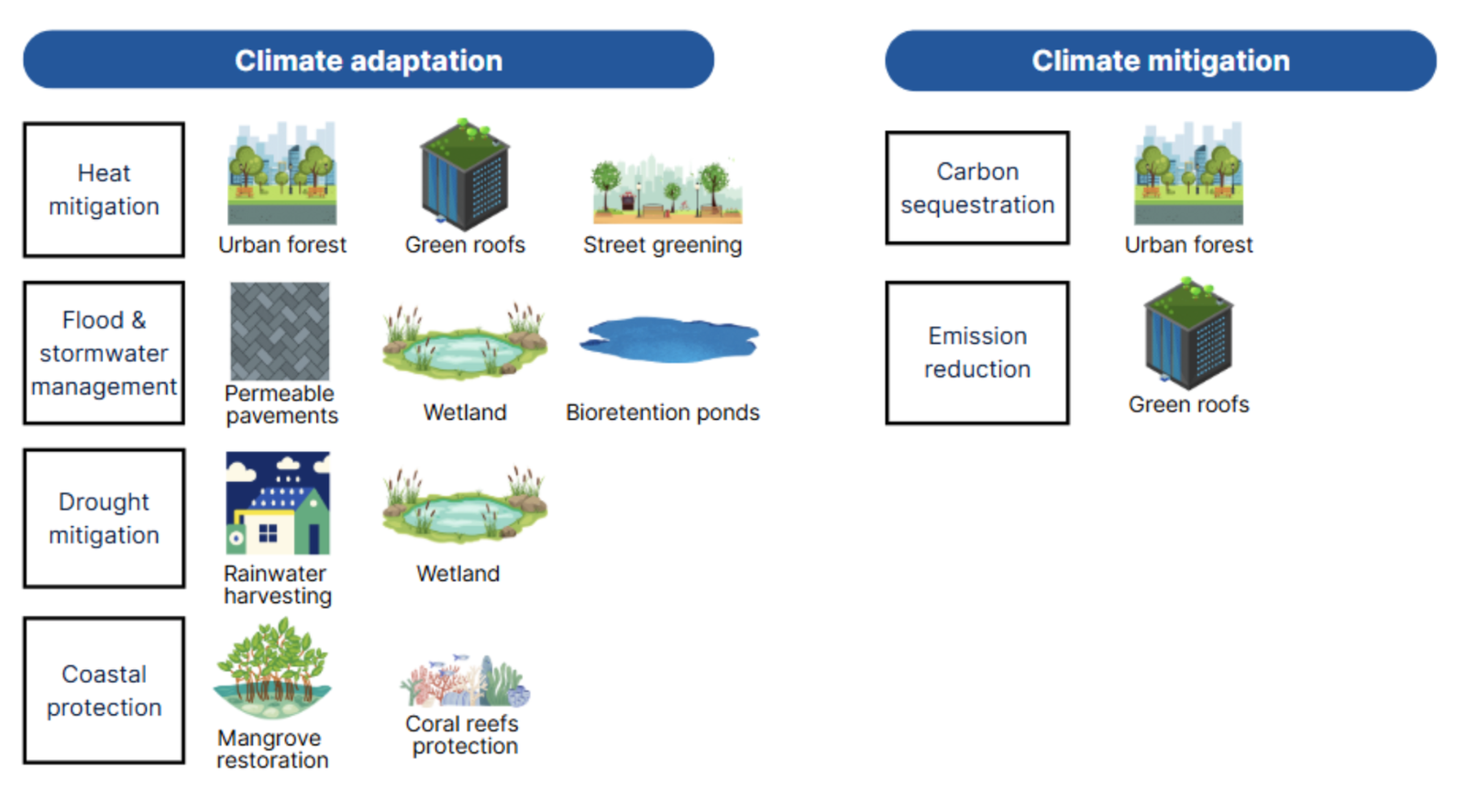

This perspective has also reshaped the water-related interventions within the context of climate policy and urban planning. Solutions to water challenges are no longer solely focused on engineering infrastructure; instead, they are increasingly recognized as essential elements of climate adaptation. In urban areas, water management—such as flood control, improved drainage, and rainwater harvesting—are often categorized as climate adaptation strategies to address the impact of climate change, rather than addressing its cause nor reducing GHG emissions. As cities adapt to climate change, water management becomes central to urban resilience strategies.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are among the most vital tools in water management. NbS approaches such as urban wetlands, permeable paving, and green roofs will support natural processes of water infiltration, absorption, and ecosystem restoration. Besides its multi-benefits, NBSs are valued as a good alternative to traditional infrastructure, which is likely to achieve more successful results (Alves, A., Gersonius, B., Kapelan, Z., Vojinovic, Z. & Sanchez, A., 2019).

Examples of various urban NbS, both for climate adaptation and mitigation.

The investment gap in climate adaptation in water systems

Urban climate finance has been a growing discussion since 1992, when the “financial resources” context was embedded in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) document. A significant turning point of climate finance came at COP15 in Copenhagen, where developed countries committed to mobilize USD 100 billion per year by 2020 to support mitigation and adaptation efforts in developing countries. Despite this commitment, funding directed toward climate adaptation remains limited. According to the Climate Policy Initiative (2021), only 1.2% of urban climate finance is directed toward adaptation and resilience, highlighting a severe imbalance in funding that leaves urban areas vulnerable to climate-related risks. This level of investment falls far short of what is required to mitigate the long term environmental and socio-economic impacts of climate-related disaster.

Compared to climate mitigation, the investment in climate adaptation is inadequate, particularly in relation to urban planning and water management (United Nations Programme, 2023). Data from CPI stated that most of the climate finance was spent on the energy sector (20 USD from 2016 – 2019) (Climate Policy Initiative, 2021), and very little was spent on adaptation measures. This is largely attributed to the stigma surrounding climate adaptation, which is often perceived as non-commercial, despite requiring substantial investment. Consequently, available funding is dominated by the public sector, as adaptation projects are less attractive to the private sector.

According to the OECD (2020) solutions related to water supply, sanitation and flood protection often lack commercial appeal due to their long-term benefits, site-specific design, and reliance on public financing. To date, few countries have started addressing the problem of funding water system adaptation. Some have begun to integrate water system adaptation into their budgetary frameworks through projects supported by global funding sources. Others have created dedicated climate adaptation funds, where water-related measures are included.

This broader funding gap is even more visible when examining targeted efforts such as Nature-based Solutions.

Why Nature-based Solutions struggle to scale

There are several reasons why adaptation measures–particularly NbS–struggle to scale. First, major systemic barriers, where inadequate and inefficient regulatory, governance, and funding structures limit the implementation. Second, NbS suffers faces a lack of expertise and real-world experience in developing bankable projects, especially in urban contexts.

However, studies (e.g., Cortinovis et al. 2022) show that when implemented systematically—through a mix of small and medium-scale projects—NbS can provide cumulative, city-wide resilience benefits.

Building an ecosystem for water management innovation and adaptation

To solve complex water management challenges, a paradigm shift from fragmented, one-off solutions to an integrated ecosystem–where innovation is driven by cross-sector collaboration, local context, and measurable impact–is pivotal.

Urban water challenges are highly context-specific, influenced by local climate, infrastructure, and governance. No single approach or actor can address them in isolation. This complexity calls for adaptive, collaborative, and scalable solutions. In this context, innovation becomes essential.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) can appeal to the private sector when they open up new revenue opportunities, enhance the resilience of business operations, lower expenses, or strengthen reputation and purpose. The private sector may engage as investors, developers, providers of market infrastructure, clients, or beneficiaries. In recent years, several initiatives driven by private entities have been launched.

Technology adaptation must be locally grounded

Innovation enables scalable and replicable solutions, creating new pathways for investment in climate adaptation. When backed by risk-sharing from the public sector, private actors can co-develop delivery models, pilot scalable solutions, and develop technologies (United Nations Programme, 2021). However, for innovation to be truly effective, it must be rooted in local needs, capacities, and ecological realities. It is crucial to co-design the technologies along with the communities and tailor the solutions based on their socio-environmental context–therefore it is more likely to be adopted and maintained.

Impact measurement as a catalyst for climate adaptation finance

One of the biggest barriers to financing adaptation—especially in water and NbS—is the lack of standardized impact measurement. Unlike mitigation, which can be quantified through emissions reduction, adaptation outcomes are often long-term, site-specific, and harder to measure. This makes it difficult to attract private investment. Due to inadequate impact tracking and a lack of knowledge about returns, private funding presently accounts for just 14% of NbS funding (United Nations Programme, 2021).

Therefore, pilot projects must demonstrate measurable impact—not only in water retention or flood reduction but also in social and ecological co-benefits. Strong metrics increase investor confidence by offering predictable returns, manageable risks, and clear accountability. In order to validate and increase adaptation investments, metrics that monitor results like decreased susceptibility, increased resilience, or prevented losses are crucial (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022).

Cross-sector collaboration accelerates scaling and mainstreaming

The data from CPI (2021) shows that 72% of non-profit-led projects focus on empowering marginalized communities. In contrast, profit organizations are less active in this domain but play a key role in advancing technology-driven, innovative, and profit-generating solutions. However, sustainable implementation of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) requires a blended approach—one that combines social impact with technological and financial viability.

This is where cross-sector collaboration becomes essential. Each actor brings distinct strengths: Nonprofits provide community engagement and equity-focused frameworks, while the private sector drives innovation and financial models. Together they can work through mechanisms like by pursuing new investment products and market exposures, such as blended financing, carbon finance, and green infrastructure.

Through technical assistance, financial and regulatory incentives, early-stage company development support, and fiscal measures that are in line with environmental results, increase the number of commercially viable projects and businesses that incorporate NbS into their business model.